When I was a child my father would dress up as a nun to be Master of Ceremonies at local churches’ roasts of their priests. Dad was introduced as the visiting Sr. Virginia allowing him to add “Virgin for short, but not for long.”

When I was a child my father would dress up as a nun to be Master of Ceremonies at local churches’ roasts of their priests. Dad was introduced as the visiting Sr. Virginia allowing him to add “Virgin for short, but not for long.”

Since apples don’t fall far from the tree, I’ve channeled his interest in Brides of Christ into a series of articles, photos, videos and book chapters on the lives of the cloistered in Mexico.

Did you know each nun writes an autobiography? The autobiography helps the priest she confesses to better understand her upbringing and point of view.

The most famous nun autobiography is St. Therese of the Little Flower’s. Therese joined the convent as a French, late 1800s, adolescent and was dead by 24. She’d be forgotten if not for her autobiography.

Therese described people as being God’s gardens. Sure, Sunflowers are dramatic and tall while roses are the prettiest, yet no one wants a garden of just sunflowers or roses. The beauty is in the variety.

For Therese, she was a wildflower, those tiny, industrious flowers that bloom close to the dirt, hence her name Therese of the Little Flower.

Recently I stumbled upon the writings of a Creole (person of Spanish lineage born in Mexico) nun from the late 1600s, smack dab during the Inquisition (1520 to 1820). The nun wrote 12 volumes (2000 plus pages) of her life growing up on a hacienda as she entered the convent two decades later than the norm. Consequently Juana, better known as Madre Maria de San Jose, had a lot to say.

Much of what Madre Maria de San Jose wrote was fascinating reflecting the life of a Creole hacienda woman. Suffice to say life wasn’t easy.

Parents

Both of her parents were natives of Puebla being of good social standing as descendants of the conquistadors settling what had been indigenous land.

Both of her parents were natives of Puebla being of good social standing as descendants of the conquistadors settling what had been indigenous land.

Her mother brought wealth into the marriage being the daughter of a town councilman and received a considerable dowry. Between both her parents they owned two haciendas outside of Puebla where they raised one son and eight daughters.

Mom tired of constant pregnancy, plus her two miscarriages, so she prolonged breast feeding in an attempt at birth control. With nine living children, the effectiveness was dubious.

Upon marriage the mother entered the hacienda at 19 and never left it.

The family grew poor over the marriage’s course and even poorer when the future nun’s father died.

Hacienda Life

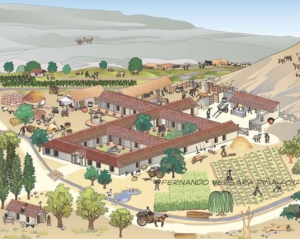

Madre Maria de San Jose was raised on one of 300 haciendas outside of Puebla, the most important Creole center of Mexico. The nun notes that in 21 years the family made two trips to Puebla. Her life was the hacienda.

Apparently Madre Maria de San Jose’s parents weren’t that affluent as most Creoles visited their haciendas only during harvest season. Madre Maria de San Jose lived at a hacienda full-time.

Apparently Madre Maria de San Jose’s parents weren’t that affluent as most Creoles visited their haciendas only during harvest season. Madre Maria de San Jose lived at a hacienda full-time.

The hacienda, in addition to wheat fields, featured the house, chapel, garden and orchard. Mass could be said at the chapel making the hacienda a village and the couple’s children were baptized there. The hacienda was also a station for lodging Franciscan friars traveling to rural areas.

The hacienda house had three rooms – a parlor and two bedrooms divided by gender for the large family and servants.

Haciendas were rarely in one family more than two or three generations. The widow inherited debt along with the hacienda plus subdividing the hacienda’s land among children often terminated the business of farming.

Aside: You can see similar results in today’s San Miguel de Allende when parents leave the family home to all thirteen kids. Rarely do thirteen grown children get along much less their spouses so the home becomes rife with strife as they’ll never get everyone to agree on selling the property.

Childhood

Juana (later called Madre Maria de San Jose) spent her youth with young girls from local Creole families and daughters of indigenous servants. They congregated in the garden playing at grinding corn and wheat (using sand) for making tortillas and bread.

Juana (later called Madre Maria de San Jose) spent her youth with young girls from local Creole families and daughters of indigenous servants. They congregated in the garden playing at grinding corn and wheat (using sand) for making tortillas and bread.

Juana’s father died when she was nine. Also at nine is when a girl started producing clothing and food items.

Starting at 9 AM women did needlework together in the house parlor in silence. Then the midday meal of bread and tortillas was served. Next girls fed the dogs and chickens prior to a siesta until 5 PM. Then women went back to their needlework continuing work on religious images of a Virgin or saint.

At 8 PM the entire family said a rosary before the evening meal then another hour of needlework while a man read aloud. If not doing needlework a woman spun fiber from the century plant in silence while listening. Upon her father’s death, all the women slept in one room and her brother in another.

At 8 PM the entire family said a rosary before the evening meal then another hour of needlework while a man read aloud. If not doing needlework a woman spun fiber from the century plant in silence while listening. Upon her father’s death, all the women slept in one room and her brother in another.

At the age of eleven Juana married Jesus in a vision convincing the lass she was destined to be a nun. She didn’t become an actual Bride of Christ until the very late age of 32.

To ever get to be alone Juana went to a garden shed with a hay roof used to store castoffs or host hen. It was filthy but she had no other place to go.

Girls had few options for self-expression and self-flagellation was popular believing to share in Christ’s salvation one needed to share in his suffering. For example, Juana spent years not speaking and later needed her younger sisters’ help recovering the ability to speak.

While Juana waited for her chance to join a convent it wasn’t easy to be holy on the hacienda. A non-nun could be brought before the Inquisition council and denounced as a false holy woman if acting too pious. Juana was wise to hide alone in the garden saying prayers and self-flagellating.

After a certain age a young Creole woman was discouraged from spending too much time with any servant girl she grew up with. Such closeness invited claims of lesbianism, causing the servant to flee the hacienda in fear for they had zero power or hopes for a dowry.

Siblings

As the sixth daughter Juana had little chance of having a two to four thousand pesos dowry necessary to enter a convent.

Older sisters Augustina and Ana neither married nor took the veil living their lives out on the hacienda. This worked best for their brother, Thomas, who never needed to pay a dowry for either.

The next two sisters, Leonor and Francisca entered the convent. Juana was young at the time and had no idea how Leonor got in. With Francesca their brother got in a fight with the bishop so Francesca couldn’t take her final vows for six years until the bishop formed a convent for poor Creoles that didn’t have dowries.

The convent was formed in large part thanks to their mother’s behind the scenes toadying to the bishop while Thomas publicly fought feeling his sisters belonged in a more prestigious convent recognized by the pope.

Sisters closest in age to Juana (Maria, Isabel and Catalina) married with the promise of an inheritance when their mother died. A cash dowry was required by a convent, for marriage a dowry was based on goods or the promise of an inheritance. Marriage offered Thomas a less immediate drain of economic resources and the possibly of establishing a tie with a wealthy family.

Of the eight sisters – two stayed on the hacienda, two became nuns (one an abbess of her convent) while three entered prominent families and moved to Puebla with one of them dying in childbirth.

The brother, Thomas, got a formal education in Puebla while his sisters stayed at home to learn needlework and womanly virtues like rudimentary reading by their mother.

Since Tomas had no inclination to enter religion, or any other profession, he came home to the hacienda.

Juana’s parents, then bother, exercised the most authority over family decisions, while the sisters’ authority depended on birth order. Only Juana’s younger sisters and indigenous servants were beneath her. Indigenous servants made no decisions, both part and separate from the household.

When Juana sought to institute a life outside the household routine, family members with greater authority prevented her.

On becoming a widow the mother assumed full ownership of the haciendas and guardianship of her children, yet Tomas ran the haciendas as head of the patriarchal system and not based on ownership.

Thomas was head of household controlling his sisters’ fates. He was difficult being a hindrance to Juana’s vocation.

Sisters’ reactions varied. Francisca wanted Maria to join a convent with her but any dowry belonged to her first and foremost while Augustina wanted her to remain on the hacienda.

A nun cut ties with family members and was considered dead to the secular world. The spiritual family had nuns for sisters, abbess a mother figure, priests as fathers and Christ as their husband. Some of Juana’s family members bulked at the idea.

Conclusion

Tensions and conflicts existed in the power structure of Maria’s rural Creole family. The subtle competition between mother and son for authority to make family decisions, the competition among sisters for a dowry and religious vocations plus the social pressure of Creoles to avoid close association with servants all expose the realities of hacienda life.

Formed by the isolation of the hacienda, routines of family life and power struggles of household members were caused by differences in gender, birth order and caste. Madre Maria de San Jose revealed women’s roles, details of domestic life, the power of the feminine and spirituality.

After 10 years in her Puebla order Madre Maria de San Jose left her convent as an abbess to found a daughter convent for Our Lady of Solitude in Oaxaca.

After 10 years in her Puebla order Madre Maria de San Jose left her convent as an abbess to found a daughter convent for Our Lady of Solitude in Oaxaca.

She died in the Oaxaca convent at 63 in 1719 leaving behind the most detailed documentation on the role of women on the haciendas of her era.