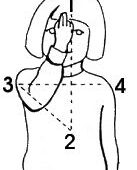

Gambol into the lobby of the Hotel Real de Minas, cross the courtyard of the Allende Institute or visit any antique store in town and you’re bound to view a painting of a 18th or 19th century nun wearing a crown of flowers. Who is she? What does she represent? Is she relevant beyond an old-timey subcategory of portraiture?

The crowned nuns, named for the elaborate floral crowns atop their heads, are accompanied by objects such as candles, a ring, an infant state of Jesus and a whole lot of flowers. These lavish portraits were made on the occasion of a nun’s profession (when she officially entered a cloistered convent accepting her vows of chastity, obedience and alike).

The crowned nuns, named for the elaborate floral crowns atop their heads, are accompanied by objects such as candles, a ring, an infant state of Jesus and a whole lot of flowers. These lavish portraits were made on the occasion of a nun’s profession (when she officially entered a cloistered convent accepting her vows of chastity, obedience and alike).

In Colonial Mexico there were 52 cloistered convents (22 in Mexico City, 11 in Puebla, 5 in Oaxaca, with the others distributed across Mexico including here in San Miguel de Allende). Nuns were understood to be integral to the health of a community since they prayed on behalf of people to help shorten one’s time in Purgatory.

Nuns lived cloistered in a convent, meaning that once they entered they did not leave except to create another convent somewhere else.

A church was often connected to a convent; while nuns did not enter it, their presence could be heard or sensed through a grill that lay people could observe while in church like seen today in the temple of the Immaculate Conception.

Nuns became increasingly important in the 17th and 18th centuries. The injection of silver into the economy meant more families acquired wealth, allowing them to pay the dowry needed to permit their daughters (normally the oldest) entry into a convent. A marriage dowry was more expensive than one needed for a convent, so becoming a nun was often a beneficial alternative for young women of elite families. While nuns might never see their families again, many could live a life of comfort inside the convent.

Nuns became increasingly important in the 17th and 18th centuries. The injection of silver into the economy meant more families acquired wealth, allowing them to pay the dowry needed to permit their daughters (normally the oldest) entry into a convent. A marriage dowry was more expensive than one needed for a convent, so becoming a nun was often a beneficial alternative for young women of elite families. While nuns might never see their families again, many could live a life of comfort inside the convent.

Some orders, like here in San Miguel de Allende, had servants, could play music, and had libraries to educate themselves. The famous feminist nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, had a large, exceptional library with scientific instruments at her disposal in Mexico City.

Final orders were a marriage of the young nun to Christ, commonly called a Bride of Christ. Interestingly, the statue of Jesus as a baby in most crowned nun portraits suggests that the nun will perform the maternal role becoming at once both bride to Christ and his mother.

The infant Jesus also represented the babies the nun would not have. Later, after her death, the baby Jesus often returned to her family becoming part of the nativity set. A nativity set with multiple baby Jesus images represents a family tree with many nuns.

Portraits of crowned nuns were typically commissioned by a nun’s family as a last act of vanity before their daughter joined the convent. The extravagant clothing and flowering paraphernalia was costly, and a portrait like this advertised a family’ wealth.

Indigenous women weren’t allowed to become nuns until 1724 though they were always present in the convent as servants. It was likely these women taught the Creole and Spanish nuns the Mesoamerican art of making flower garlands and crowns used in the paintings. Ancient codices featured Aztec goddesses wearing flower crowns and details on how to make them.

Women who entered the convent were said to become ‘dead to the world.’ Their portraits weren’t captured again, and again in floral finery, until they were literally dead.

Women who entered the convent were said to become ‘dead to the world.’ Their portraits weren’t captured again, and again in floral finery, until they were literally dead.

These portraits also functioned as official documents recounting their daughter’s lineage. They include lengthy inscriptions noting the name of the nun, her parents’ names (and that she is their legitimate daughter), the date of her profession, the name of the convent that she entered, and sometimes, the date of her death.

The portraits visually expressed the popular belief that Spanish America was the site of the new earthly paradise whose most precious flowers were its virgin nuns. The result was an amplification of the nuns’ spiritual supremacy and the projection of a sense of solidarity among Mexico’s nuns regardless of religious order or ethnic identity in iconic images.

Crowned nun portraits are exclusive to Mexico featuring nuns of all types. Over in Spain only nuns who were an abbess or convent founder got painted.

It is important to remember that at that time, women did not have the right to free speech or to vote in Mexico, or anyplace else in the world.

In today’s world Banamex bank owns the largest collection of crowned nun portraits.

Now, of course, any woman can enjoy a floral crown from the Mexican Maria doll to New York’s most famous Jewish nanny!

Now, of course, any woman can enjoy a floral crown from the Mexican Maria doll to New York’s most famous Jewish nanny!